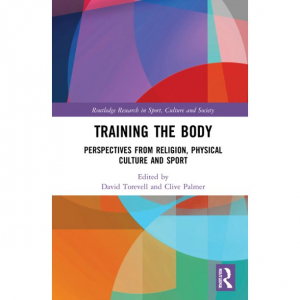

Training the Body

The following is an excerpt from David Torevell (featured), Clive Palmer, and Paul Rowan, eds., Training the Body: Perspectives from Sport, Physical Culture and Religion (London: Routledge, 2022).

The aim of Training the Body: Perspectives from Sport, Physical Culture and Religion is to introduce central ideas and spark further thinking about the transdisciplinary debate surrounding sport, physical culture and religion in relation to bodily training. Discussions between sport, physical culture and religion have the potential to become enriching learning experiences for all those involved if they are based on honest and receptive dialogue; the authors are keen to facilitate such exchanges in schools, colleges and universities. Clearly, religion has much to learn from those involved in sports and physical culture training. And vice versa. The multifaith nature of the text allows readers to draw from a wide range of spiritual perspectives – Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, Judaism and Christianity. There are four sections to the book: Personhood, Virtue, Asceticism and Aesthetics, and Education, Gender and Mental Health. These constitute broad themes. Inevitably, there is some overlap across the sections. The text ends with questions for further discussion and research.

Over the past 30 years, the body has become a contested site for discussion across a whole range of academic subjects; we hope this work will add to the bourgeoning interest in this topic. What is shared by all the contributors is that the body plays a pivotal role in the thinking and practice of their disciplines.

Personhood

Any discussion of corporeality and the somatic inevitably touches on issues surrounding personhood. Contributors point to this dilemma by addressing the myriad ways in which the relationships between the body, the mind and the spirit have been conceived. The authors argue that it is in the actual doing of physical practice that personal change starts to occur. For religious practitioners the regular movement, gesturing and disciplining of the body become the mode for the movement towards sacrality and transcendence. The potentially transfigured body, however, is always open to being strengthened and/or damaged as part of this endeavour.

Technology and the Future

The book delineates how specific religious and sports-related somatic techniques and practices within regular and disciplined training regimes, often with long histories, have the potential (or not) to unlock energy, increase physical stamina, foster the virtues and enhance spiritual dispositions necessary to live a life to the full. Trothen’s essay on technological ‘enhancements’ in sport in an age of biohacking, artificial intelligence and transhumanism is an important one to consider.

Virtue

Related to the complexity of who we are is the question: who might we become? Human beings are capable of immense change over a lifetime(s) for good or ill and this dynamic has a central bearing on religious and sporting transformation allied to changes in the body. The book endorses the view that a person is assisted in leading a virtuous and happy life only by the inclusion of a ludic element in their lives. St Thomas Aquinas argued that there is ‘a virtue about games’ primarily because it has to do with moderation. A virtuous person, by this account, should not work all the time; he or she need periods of renewal through strenuous movement, exercise and then rest.

To some degree then, sport, physical culture and religion all concern themselves with the development of the virtuous and ethical person and a transition from and beyond the moral spiritual space in which participants currently find themselves. This issue is interconnected with the primary motivations and objectives involved in the three disciplines. Each is concerned with combat and thus has a martial element embedded in it. Religious practitioners tend to see their primary challenge in terms of ethical combat and emphasize the primacy of self-combat. Torevell outlines how Eastern religious and martial arts’ understandings of the training of the body invariably include the notion of an intense struggle to release the entrapped self from mundane consumerist conditioning so that it might raise itself above platitudinous acquiescence. The battle or combat is internal, involving a rewarding journey of inwardness as practitioners seek to delve into their inner lives more deeply. Rowan’s contribution asks readers to ponder on the ‘why’ and meaning of training apart from its acquisition of well-honed techniques and skills.

Asceticism and Aesthetics

The book notes how there is an intriguing symbiosis between the cultivation of beauty in sport and religion and its ascetical underpinnings. Any religious understanding of the training of the body is necessarily connected to wise asceticism, and this sets up a crucial debate about strict training regimes in sport and physical culture, human endurance and the boundaries to be observed when striving for betterment. Religious and sport-related understanding of the training of the body is not about artificially adding to the body but rather paring it back. Grecic notes that early Chinese philosophy deeply influenced the State’s approach to physical education and a central teaching on restraint is reflected in its sports training.

Those who participate in sport and physical culture are able to become a ‘work of art’, bringing delight and joy to themselves and others by the grace and enrapturing spectacle of their performances, sometimes the graceful spinning bodily descent of a high diver or the elegant poise of a gymnast flying in the air on the dancefloor, to take two examples. Vanysacker claims that sport can offer us a chance to take part in beautiful moments, or to see these take place. In this way, sport has the potential to remind us that beauty is one of the ways we can encounter God.

Education, Mental Health and Gender

There are important interdisciplinary debates to be conducted in the future about the educational implications of ‘training the body’ in religion and sport. Mental health is one of them. The gendered nature of training the body is a significant strand in this text and Blazer and Borish deal specifically with this issue. The former is highly critical of present-day physical instruction in the United States, which continues to fall into the trap of muscular Christianity which encourages an approach guilty of gender essentialism. Human beings experience highly gendered cultural expectations and often unknowingly adjust their behaviours, thoughts and desires to reflect these presumed norms. Borish’s examination of Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Associations – Jewish Ys – in the early twentieth-century America demonstrates how they strove to promote the religious and physical welfare of Jews.

We hope this book will stimulate further reflection and research on the trans-disciplinary topic of religion, sport and physical culture and how each considers the significance and purpose of any training of the body. Contributors have set in motion a dialogue which they trust will continue to bear fruit in the future. There is a need for voices to emerge that will articulate the overlapping dynamics between religion, sport and physical culture. The book encourages this emergence.

The book delineates how specific religious and sports-related somatic techniques and practices within regular and disciplined training regimes, often with long histories, have the potential (or not) to unlock energy, increase physical stamina, foster the virtues and enhance spiritual dispositions necessary to live a life to the full.

— DAVID TOREVELL

Listen to the companion podcast.

Order your copy today from your favorite bookseller.