Teaching by…Following? The Case Study of a Religion and Sport Class

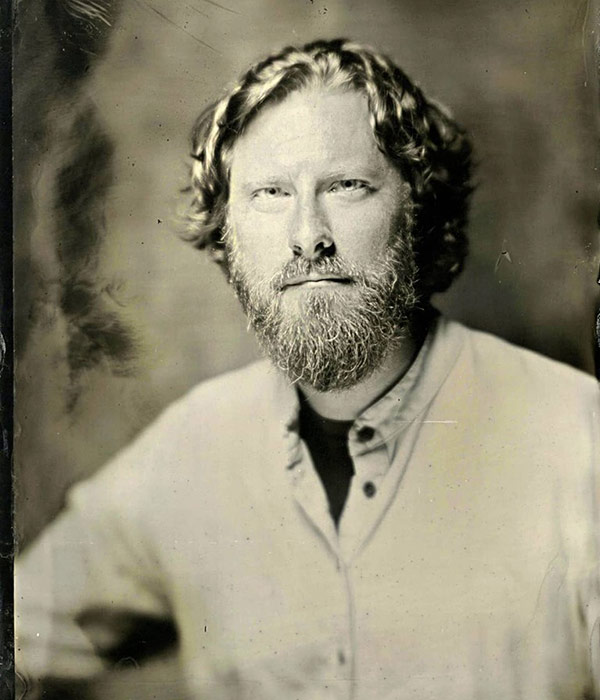

DECEMBER 2, 2020 / BY ANDREW R. MEYER, PHD. / ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, BAYLOR UNIVERSITY

Students are producers of knowledge, not just consumers. Take my Religion and Sport course at Baylor University as an example.

Like many professors I know, I usually make good connections with my students, and I teach them what I deem to be the most important and interesting facets of the relationship between religion and sport today.

Specifically, I weave into my course Muscular Christian influences on modern sport with Lance Armstrong’s embodiment of such values—these are two areas I’ve researched. I discuss how sport and religion play significant roles in societies around the globe. I encourage them to see more than just Tebowing, church softball leagues, and thanking Jesus after a win. I want them to understand the significant spiritual and religious nature of our the physical expenditure of energy, and I want them to engage in deeper conversations about the powerful moral meaning and influence sport and athletes have for individual lives and within communities.

But to get from touchdown prayers and church softball leagues to the spiritual and religious nature of human movement and meaning, I had to stop treating them like consumers and start treating them like producers.

In 2017, I was named a Baylor Teaching Fellow. My specific charge was to incorporate Christian virtues into my course. This gave me a chance to reimagine how I taught Religion and Sport.

My father always echoed that well known saying that ‘sport builds character.’ This always struck me as funny, because he also said that shoveling snow off our extra-long driveway during New England winters also built character. I didn’t see the connection! So I brought a similar question to my students: “Does sport build Christian character, and if so, what kind of character is it building?” Baylor is a Christian university, and my mostly Christian students thought they knew the answer to this question. Honestly, I did, too. But over the past six semesters I had no idea what would emerge.

The first thing I did with the course was to LET GO! I allowed myself to not pre-package the course for my students as consumers. Instead I found a list of Christian character-building programs, and before the syllabus is set for every class, I let the students choose which Christian character traits we explore each semester. The act of inviting my students to participate in establishing the structure and nature of the course brings them immediately into a conversation with the essential question of the course. And they feel empowered to produce.

The results have been astounding. I have watched my students become vulnerable, sharing life experiences and building relationships. After the first few weeks of exploration, students begin to see connections between traits. They develop larger narratives about these Christian traits in the context of sport, identifying how the traits function in our society and in their religion. The students and I share personal stories, creating deeper relationships that did not occur in prior semesters.

By stepping out of the way, and following my students, I have invited them to be partners in the production of knowledge around religion and sport, not just consumers.

I have learned a few lessons from following the lead of my students.

- First, sport as we know it today will absolutely fail to live up to the ideals we have bestowed upon it because it is a human enterprise. Even from a religious perspective, the failure of athletes, organizations and institutions to promote Christian character is obvious and widespread.

- Second, despite all of this, my students are inspired, eager, and excited to learn about the Christian moral values (character traits) found in contemporary sport. This doesn’t happen immediately—it still takes time for them to see the nuanced nature of sport and the power of its ideals—but in continuing to approach these issues with our students, as empowered leaders and knowledge producers, we can promote change toward a more equitable, value-based, and empowering sport environment.

- Third, I did not have to let go of my standards as an educator when I invited my students in. I have retained my core aim of challenging them to think for themselves and critically examine the world around them, while also inviting them into the decision-making processes of the course. I must still remember to meet them where they are. My old standards were about delivering the course material I deemed to be important. But, in this student-led approach, I made room for my students to surprise me, creating new conversations and insights on the course content.

I may be a good teacher, but I learned that I can never teach to students what they can produce for themselves.

Sport, as we know it today, will absolutely fail to live up to the ideals we have bestowed upon it because it is a human enterprise.

— ANDREW R. MEYER, PhD.

Andrew Meyer is an Associate Professor at Baylor University. He likes long bike rides and posing for frontier-style photos that make Davy Crockett jealous.

Listen to the companion podcast.